Interpreting ASTM D4169 Schedule A: What Manual Handling Data Really Tells You

For the ASTM D4169 distribution testing standard, Schedule A is often summarized as a “drop test.” While that description is technically correct, it significantly understates the value of the data produced. Schedule A is not simply about whether a package survives a fall—it is about how a packaging system responds to discrete, human-driven or automated handling events, and what those responses reveal about design robustness, risk, and validation readiness.

For medical device manufacturers, understanding how to interpret Schedule A data is critical to making sound packaging decisions early in development and during validation. Given that this is not a pass/fail test according to the standard, there are many interpretations and implications as to what the data means.

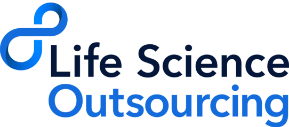

What ASTM D4169 Schedule A Is Designed to Simulate

Schedule A represents manual handling hazards, including:

- Lifting and repositioning

- Set-down events

- Accidental drops during handling or sorting

- Short-duration, high-energy impacts caused by human interaction

Unlike vibration or compression schedules, Schedule A isolates individual handling events rather than cumulative transport exposure. This is why Schedule A frequently appears at both the beginning and end of distribution cycles such as DC-13—it brackets the distribution environment with realistic human handling risk.

What Data Schedule A Actually Produces

Schedule A does not generate a single numeric output. Instead, it produces observational and comparative data that must be interpreted in context.

Typical data outputs include:

- Visible damage to the outer package beyond cosmetic scuffing or scrunching

- Rigid seal deformation or stress whitening for clear polymer substrates

- Seal creep for products that are too heavy or have incompatible shapes for their sterile barrier packaging

- Corner, edge, or face failures

- Changes in package geometry needed or preparedness

- Internal product movement or contact

The real value of Schedule A lies not in whether damage occurs, but where, how, and under what conditions it occurs.

How to Interpret Schedule A Results Correctly

Location of Damage Matters More Than Appearance

A common mistake is to focus on how severe damage looks rather than where it occurs. Cosmetic scuffing on a non-critical surface is fundamentally different from deformation near:

- Taped surfaces or edges

- Fold lines

- Seals for sterile barriers

- Material transitions

- Device contact points

Damage at interfaces tied to sterile barrier integrity or device protection carries far more risk than superficial abrasion.

Engineering perspective:

Cosmetic damage can be acceptable. Damage at functional interfaces rarely is.

Repeatability Signals Design Weakness

When multiple samples fail in:

- The same orientation

- The same location

- Under the same drop condition

The issue is not random handling—it is a deterministic design limitation.

Schedule A is especially effective at exposing:

- Asymmetric package designs

- Uneven mass distribution

- Insufficient corner protection

- Seal orientation sensitivity

Repeatable, systematic failures are not noise; they are design feedback.

Passing Is Not the Same as Being Robust

A package can “pass” Schedule A and still be weakened, which could depend on the assurance level is chosen.

Engineers should assess:

- Whether deformation is elastic or permanent

- Whether package geometry needs to be changed

- Whether downstream tests (vibration or compression) are now compromised or produce misleading data

- The correct assurance level should produce the most real-world worst-case scenario

Schedule A damage can act as a precursor failure, increasing risk later in the distribution sequence which would lead to cumulative stresses and outcomes.

Interpreting Failures Without Overreacting

Not every Schedule A failure requires immediate redesign. Results should be interpreted through risk context, including:

- Impact on sterile barrier integrity

- Effect on device function or safety

- Label legibility and usability

- Regulatory and patient risk implications

For medical packaging, the core question is:

Does this failure create a credible risk to sterility, device function, regulatory compliance, or patient safety?

If the answer is no—and the rationale is documented—the outcome may still be acceptable.

Schedule A as a Diagnostic Tool

Experienced packaging engineers often use Schedule A early in development because it:

- Is fast to execute

- Is cost-effective

- Reveals gross design weaknesses quickly

Schedule A data frequently informs:

- Cushioning selection

- Headspace allowances

- Package orientation controls

- Shipping container configurations

- Material transitions

- Device retention strategies

Learning from Schedule A failures early is far preferable to discovering them late in validation, or even worse, in the field causing costly and embarrassing recalls.

Common Misinterpretations That Undermine Validation

Avoid these common pitfalls:

- Choosing a less intense assurance level so Schedule A isn’t a worst-case test

- Using Schedule A as a standalone to claim distribution robustness

- Ignoring minor but repeatable deformation or shipping container damage

- Repeating Schedule A until it “passes” without a shipping configuration or sterile barrier system design change

Repeated testing without modification is not validation—it is data erosion.

How Auditors and Regulators View Schedule A Data

Regulators and auditors do not expect:

- Zero damage

- Perfect aesthetics

They do expect:

- Clear documentation of observed damage

- Logical interpretation tied to risk

- Alignment with ISO 11607 and ISO 14971 principles

A well-justified Schedule A “failure” is often more defensible than a superficial “pass.”

Expert Perspective from LSO

“Schedule A is one of the most revealing parts of ASTM D4169 because it shows you how a package behaves when people interact with it—not necessarily machines or other packages. When failures are repeatable, they’re telling you something very specific about the design. Ignoring that data almost always shows up later in validation or in the field – when it is a lot harder to fix than it was to change in the beginning of packaging design.”

— Matthew Emrick, Packaging Specialist, Life Science Outsourcing

The Real Value of Schedule A

Schedule A is not about proving that a package is strong. It is about understanding how it fails under human handling and whether those failures matter.

When interpreted correctly, Schedule A:

- Reduces late-stage validation risk

- Improves downstream test outcomes

- Strengthens packaging design decisions

- Supports defensible regulatory justification

Final Engineering Perspective

ASTM D4169 Schedule A is best viewed as a diagnostic lens, not a verdict. The data it produces is most valuable when interpreted with engineering judgment, risk awareness, and an understanding of how handling damage interacts with later distribution hazards.

When teams treat Schedule A as a learning tool rather than a checkbox, it consistently improves both package design and validation quality.